Like many programs broadcast on British television in the 1950's, Nigel Kneale's The Creature (1955) was not recorded on either of the nights it was performed. The internet informs me some tele-snaps exist, but those would mostly tell me whether the set designs or the effects were on a par with those of the later film adaptation The Abominable Snowman (1957), not how the stories differ or the performances compare. I would still hope for a flickery kinescope version to turn up in the BBC archives somewhere, because there are ways in which the movie feels very much like a television production as it is—a handful of characters, a couple of sets, a lot of the power of suggestion—and I would love to know what changed in the transition from small to big screen. There are also ways in which I'm surprised it wasn't a radio show, but I have that a lot on the brain lately.

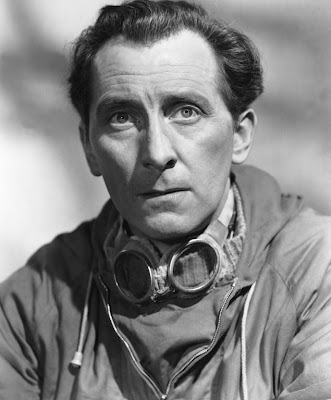

The plot is classic sci-fi survival horror: a Himalayan expedition mounted to prove the existence of the yeti unravels from the fatal, traditional combination of internal dissent and external weirdness, leaving only Peter Cushing escaped to tell us . . . what? That he was mistaken? It isn't what's out there that's dangerous so much as what's in us. Dr. John Rollason is a much less flamboyant part than Cushing's Frankenstein of the same year, a former explorer who retired from serious climbing after a bad accident; he works now as a surveyor for a botanical foundation, but the old obsessiveness flares up when he's offered the chance to join a team headed by one Tom Friend on just the topic Rollason used to theorize about—the myth of the yeti, evolutionary holdouts in strange and hidden places. Cautioned by almost everyone from his wife to the lama of the local monastery against taking part in this high-altitude snipe hunt, Rollason is nonetheless as unable to resist the pull of its mystery as the young photographer who glimpsed something once on a climb that he has to see again. He gets what he wants and you can guess how much good it does him.

I will admit that for much of the film's runtime it has difficulty generating the tension this summary implies. It's a short movie and a spare script, but Cushing is the only person wound as tightly as the dialogue; it doesn't help that the budget is showing, with long shots of Midi-Pyrénées cliffs and snowfields suddenly cutting to fake powder snow and conveniently flat-floored boulder caves. The sparseness of the sets does work eventually in favor of the characters' isolation, and the story tautens as their number is reduced, so that by the sixty-minute mark the film can give us an image straight out of John Carpenter: two men who do not trust each other on the snow at night, hammering makeshift graves by the hissing light of signal flares; a spade clangs too loudly on an ice-axe and they do not speak. It still feels as though it takes forever to reach that point, and not in the good, tantalizing, Val Lewton-leaping-at-shadows kind of way. The television play was ninety minutes with an intermission. I'd love to know if Val Guest fumbled the pacing when he adapted the script for film, or if Kneale himself just never got it right.

There are some fun things before the denouement. The nationalities are like watching an American B-movie in reverse: instead of Cushing's gentle-voiced botanist being the weak link in the party, it's Forrest Tucker's brash American entrepreneur who's out of place, pushing into the heavy winter snows with a harsh jocularity that conceals ever less of his short-cut callousness, his bullying ways. A former smuggler and gunrunner, Friend tells the story that he tired of profiting from fear and hunger and turned to curiosity as an innocent, humane desire to feed, but Rollason decries him as "nothing but a cheat, a fairground trickster." His interest in the yeti is commercial, his expedition organized around cages, rifles, and traps. Betrayed, Rollason can only stay on in hopes of being damage control, the one member of the party with real climbing expertise and a feeling for the natural world. It's easy to imagine the other version in which he's more Carrington from The Thing from Another World (1951), all squeamish scientific sympathies, no stomach for action. It's Nigel Kneale, so there are paranormal touches: the photographer who seems to function, wounded and feverish, as a kind of yeti detector, glazing into a trance state whenever the creatures are near; Rollason's growing insights about the nature of the yeti suggest that he too is on their frequency, picking up their thoughts like the hollow, haunting cries that fill the valleys at night. Back at the monastery, Rollason's wife Helen (no prizes for guessing her namesake) is sensitive to the changes in mood her bespectacled English colleague wants her to write off as native superstition; instead of waiting patiently for her husband's hopeless return, she organizes an expedition of her own to rescue him when the lowering sense of wrongness, including the lama's calm insistence to the contrary, becomes impossible to bear. She's a small part, but I like that she is allowed initiative and intelligence; she is never the one asking the wide-eyed questions so the men can get on with the infodumping. Presented by Friend with a purported yeti tooth, Rollason examines it minutely with some small tool he fishes out of his pocket; his wife merely turns it over in her hands and pronounces with as much authority as her husband, "It's living ivory." And the denouement is strong, especially considering how quickly it occurs: it's not a twist ending, but it leaves the viewer with the same sting of bleakness, unsettling reinterpretations suggesting themselves even as the final words fade out.

So happy birthday, Peter Cushing. I watched a film I hadn't seen you in and I'll watch others as soon as I can find them. May you be remembered long after I've seen them all. And your cheekbones were very fine.

The plot is classic sci-fi survival horror: a Himalayan expedition mounted to prove the existence of the yeti unravels from the fatal, traditional combination of internal dissent and external weirdness, leaving only Peter Cushing escaped to tell us . . . what? That he was mistaken? It isn't what's out there that's dangerous so much as what's in us. Dr. John Rollason is a much less flamboyant part than Cushing's Frankenstein of the same year, a former explorer who retired from serious climbing after a bad accident; he works now as a surveyor for a botanical foundation, but the old obsessiveness flares up when he's offered the chance to join a team headed by one Tom Friend on just the topic Rollason used to theorize about—the myth of the yeti, evolutionary holdouts in strange and hidden places. Cautioned by almost everyone from his wife to the lama of the local monastery against taking part in this high-altitude snipe hunt, Rollason is nonetheless as unable to resist the pull of its mystery as the young photographer who glimpsed something once on a climb that he has to see again. He gets what he wants and you can guess how much good it does him.

I will admit that for much of the film's runtime it has difficulty generating the tension this summary implies. It's a short movie and a spare script, but Cushing is the only person wound as tightly as the dialogue; it doesn't help that the budget is showing, with long shots of Midi-Pyrénées cliffs and snowfields suddenly cutting to fake powder snow and conveniently flat-floored boulder caves. The sparseness of the sets does work eventually in favor of the characters' isolation, and the story tautens as their number is reduced, so that by the sixty-minute mark the film can give us an image straight out of John Carpenter: two men who do not trust each other on the snow at night, hammering makeshift graves by the hissing light of signal flares; a spade clangs too loudly on an ice-axe and they do not speak. It still feels as though it takes forever to reach that point, and not in the good, tantalizing, Val Lewton-leaping-at-shadows kind of way. The television play was ninety minutes with an intermission. I'd love to know if Val Guest fumbled the pacing when he adapted the script for film, or if Kneale himself just never got it right.

There are some fun things before the denouement. The nationalities are like watching an American B-movie in reverse: instead of Cushing's gentle-voiced botanist being the weak link in the party, it's Forrest Tucker's brash American entrepreneur who's out of place, pushing into the heavy winter snows with a harsh jocularity that conceals ever less of his short-cut callousness, his bullying ways. A former smuggler and gunrunner, Friend tells the story that he tired of profiting from fear and hunger and turned to curiosity as an innocent, humane desire to feed, but Rollason decries him as "nothing but a cheat, a fairground trickster." His interest in the yeti is commercial, his expedition organized around cages, rifles, and traps. Betrayed, Rollason can only stay on in hopes of being damage control, the one member of the party with real climbing expertise and a feeling for the natural world. It's easy to imagine the other version in which he's more Carrington from The Thing from Another World (1951), all squeamish scientific sympathies, no stomach for action. It's Nigel Kneale, so there are paranormal touches: the photographer who seems to function, wounded and feverish, as a kind of yeti detector, glazing into a trance state whenever the creatures are near; Rollason's growing insights about the nature of the yeti suggest that he too is on their frequency, picking up their thoughts like the hollow, haunting cries that fill the valleys at night. Back at the monastery, Rollason's wife Helen (no prizes for guessing her namesake) is sensitive to the changes in mood her bespectacled English colleague wants her to write off as native superstition; instead of waiting patiently for her husband's hopeless return, she organizes an expedition of her own to rescue him when the lowering sense of wrongness, including the lama's calm insistence to the contrary, becomes impossible to bear. She's a small part, but I like that she is allowed initiative and intelligence; she is never the one asking the wide-eyed questions so the men can get on with the infodumping. Presented by Friend with a purported yeti tooth, Rollason examines it minutely with some small tool he fishes out of his pocket; his wife merely turns it over in her hands and pronounces with as much authority as her husband, "It's living ivory." And the denouement is strong, especially considering how quickly it occurs: it's not a twist ending, but it leaves the viewer with the same sting of bleakness, unsettling reinterpretations suggesting themselves even as the final words fade out.

So happy birthday, Peter Cushing. I watched a film I hadn't seen you in and I'll watch others as soon as I can find them. May you be remembered long after I've seen them all. And your cheekbones were very fine.