Human knowledge? Is that reason enough?

Like many programs broadcast on British television in the 1950's, Nigel Kneale's The Creature (1955) was not recorded on either of the nights it was performed. The internet informs me some tele-snaps exist, but those would mostly tell me whether the set designs or the effects were on a par with those of the later film adaptation The Abominable Snowman (1957), not how the stories differ or the performances compare. I would still hope for a flickery kinescope version to turn up in the BBC archives somewhere, because there are ways in which the movie feels very much like a television production as it is—a handful of characters, a couple of sets, a lot of the power of suggestion—and I would love to know what changed in the transition from small to big screen. There are also ways in which I'm surprised it wasn't a radio show, but I have that a lot on the brain lately.

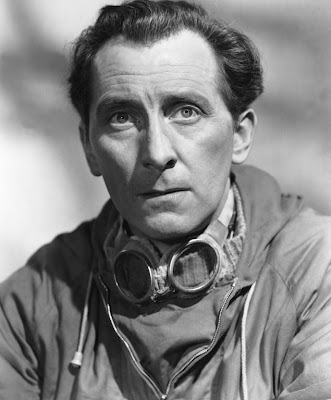

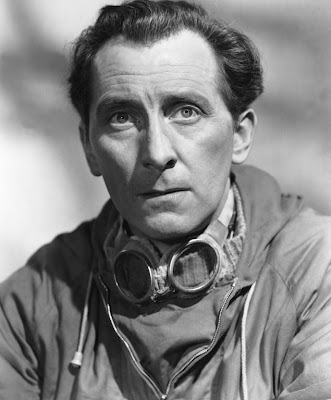

The plot is classic sci-fi survival horror: a Himalayan expedition mounted to prove the existence of the yeti unravels from the fatal, traditional combination of internal dissent and external weirdness, leaving only Peter Cushing escaped to tell us . . . what? That he was mistaken? It isn't what's out there that's dangerous so much as what's in us. Dr. John Rollason is a much less flamboyant part than Cushing's Frankenstein of the same year, a former explorer who retired from serious climbing after a bad accident; he works now as a surveyor for a botanical foundation, but the old obsessiveness flares up when he's offered the chance to join a team headed by one Tom Friend on just the topic Rollason used to theorize about—the myth of the yeti, evolutionary holdouts in strange and hidden places. Cautioned by almost everyone from his wife to the lama of the local monastery against taking part in this high-altitude snipe hunt, Rollason is nonetheless as unable to resist the pull of its mystery as the young photographer who glimpsed something once on a climb that he has to see again. He gets what he wants and you can guess how much good it does him.

I will admit that for much of the film's runtime it has difficulty generating the tension this summary implies. It's a short movie and a spare script, but Cushing is the only person wound as tightly as the dialogue; it doesn't help that the budget is showing, with long shots of Midi-Pyrénées cliffs and snowfields suddenly cutting to fake powder snow and conveniently flat-floored boulder caves. The sparseness of the sets does work eventually in favor of the characters' isolation, and the story tautens as their number is reduced, so that by the sixty-minute mark the film can give us an image straight out of John Carpenter: two men who do not trust each other on the snow at night, hammering makeshift graves by the hissing light of signal flares; a spade clangs too loudly on an ice-axe and they do not speak. It still feels as though it takes forever to reach that point, and not in the good, tantalizing, Val Lewton-leaping-at-shadows kind of way. The television play was ninety minutes with an intermission. I'd love to know if Val Guest fumbled the pacing when he adapted the script for film, or if Kneale himself just never got it right.

There are some fun things before the denouement. The nationalities are like watching an American B-movie in reverse: instead of Cushing's gentle-voiced botanist being the weak link in the party, it's Forrest Tucker's brash American entrepreneur who's out of place, pushing into the heavy winter snows with a harsh jocularity that conceals ever less of his short-cut callousness, his bullying ways. A former smuggler and gunrunner, Friend tells the story that he tired of profiting from fear and hunger and turned to curiosity as an innocent, humane desire to feed, but Rollason decries him as "nothing but a cheat, a fairground trickster." His interest in the yeti is commercial, his expedition organized around cages, rifles, and traps. Betrayed, Rollason can only stay on in hopes of being damage control, the one member of the party with real climbing expertise and a feeling for the natural world. It's easy to imagine the other version in which he's more Carrington from The Thing from Another World (1951), all squeamish scientific sympathies, no stomach for action. It's Nigel Kneale, so there are paranormal touches: the photographer who seems to function, wounded and feverish, as a kind of yeti detector, glazing into a trance state whenever the creatures are near; Rollason's growing insights about the nature of the yeti suggest that he too is on their frequency, picking up their thoughts like the hollow, haunting cries that fill the valleys at night. Back at the monastery, Rollason's wife Helen (no prizes for guessing her namesake) is sensitive to the changes in mood her bespectacled English colleague wants her to write off as native superstition; instead of waiting patiently for her husband's hopeless return, she organizes an expedition of her own to rescue him when the lowering sense of wrongness, including the lama's calm insistence to the contrary, becomes impossible to bear. She's a small part, but I like that she is allowed initiative and intelligence; she is never the one asking the wide-eyed questions so the men can get on with the infodumping. Presented by Friend with a purported yeti tooth, Rollason examines it minutely with some small tool he fishes out of his pocket; his wife merely turns it over in her hands and pronounces with as much authority as her husband, "It's living ivory." And the denouement is strong, especially considering how quickly it occurs: it's not a twist ending, but it leaves the viewer with the same sting of bleakness, unsettling reinterpretations suggesting themselves even as the final words fade out.

So happy birthday, Peter Cushing. I watched a film I hadn't seen you in and I'll watch others as soon as I can find them. May you be remembered long after I've seen them all. And your cheekbones were very fine.

The plot is classic sci-fi survival horror: a Himalayan expedition mounted to prove the existence of the yeti unravels from the fatal, traditional combination of internal dissent and external weirdness, leaving only Peter Cushing escaped to tell us . . . what? That he was mistaken? It isn't what's out there that's dangerous so much as what's in us. Dr. John Rollason is a much less flamboyant part than Cushing's Frankenstein of the same year, a former explorer who retired from serious climbing after a bad accident; he works now as a surveyor for a botanical foundation, but the old obsessiveness flares up when he's offered the chance to join a team headed by one Tom Friend on just the topic Rollason used to theorize about—the myth of the yeti, evolutionary holdouts in strange and hidden places. Cautioned by almost everyone from his wife to the lama of the local monastery against taking part in this high-altitude snipe hunt, Rollason is nonetheless as unable to resist the pull of its mystery as the young photographer who glimpsed something once on a climb that he has to see again. He gets what he wants and you can guess how much good it does him.

I will admit that for much of the film's runtime it has difficulty generating the tension this summary implies. It's a short movie and a spare script, but Cushing is the only person wound as tightly as the dialogue; it doesn't help that the budget is showing, with long shots of Midi-Pyrénées cliffs and snowfields suddenly cutting to fake powder snow and conveniently flat-floored boulder caves. The sparseness of the sets does work eventually in favor of the characters' isolation, and the story tautens as their number is reduced, so that by the sixty-minute mark the film can give us an image straight out of John Carpenter: two men who do not trust each other on the snow at night, hammering makeshift graves by the hissing light of signal flares; a spade clangs too loudly on an ice-axe and they do not speak. It still feels as though it takes forever to reach that point, and not in the good, tantalizing, Val Lewton-leaping-at-shadows kind of way. The television play was ninety minutes with an intermission. I'd love to know if Val Guest fumbled the pacing when he adapted the script for film, or if Kneale himself just never got it right.

There are some fun things before the denouement. The nationalities are like watching an American B-movie in reverse: instead of Cushing's gentle-voiced botanist being the weak link in the party, it's Forrest Tucker's brash American entrepreneur who's out of place, pushing into the heavy winter snows with a harsh jocularity that conceals ever less of his short-cut callousness, his bullying ways. A former smuggler and gunrunner, Friend tells the story that he tired of profiting from fear and hunger and turned to curiosity as an innocent, humane desire to feed, but Rollason decries him as "nothing but a cheat, a fairground trickster." His interest in the yeti is commercial, his expedition organized around cages, rifles, and traps. Betrayed, Rollason can only stay on in hopes of being damage control, the one member of the party with real climbing expertise and a feeling for the natural world. It's easy to imagine the other version in which he's more Carrington from The Thing from Another World (1951), all squeamish scientific sympathies, no stomach for action. It's Nigel Kneale, so there are paranormal touches: the photographer who seems to function, wounded and feverish, as a kind of yeti detector, glazing into a trance state whenever the creatures are near; Rollason's growing insights about the nature of the yeti suggest that he too is on their frequency, picking up their thoughts like the hollow, haunting cries that fill the valleys at night. Back at the monastery, Rollason's wife Helen (no prizes for guessing her namesake) is sensitive to the changes in mood her bespectacled English colleague wants her to write off as native superstition; instead of waiting patiently for her husband's hopeless return, she organizes an expedition of her own to rescue him when the lowering sense of wrongness, including the lama's calm insistence to the contrary, becomes impossible to bear. She's a small part, but I like that she is allowed initiative and intelligence; she is never the one asking the wide-eyed questions so the men can get on with the infodumping. Presented by Friend with a purported yeti tooth, Rollason examines it minutely with some small tool he fishes out of his pocket; his wife merely turns it over in her hands and pronounces with as much authority as her husband, "It's living ivory." And the denouement is strong, especially considering how quickly it occurs: it's not a twist ending, but it leaves the viewer with the same sting of bleakness, unsettling reinterpretations suggesting themselves even as the final words fade out.

So happy birthday, Peter Cushing. I watched a film I hadn't seen you in and I'll watch others as soon as I can find them. May you be remembered long after I've seen them all. And your cheekbones were very fine.

no subject

the fatal, traditional combination of internal dissent and external weirdness, --loved that. Also, what you said about the wife being allowed initiative and intelligence.

no subject

SPOILERS OKAY PEOPLE WHO HAVE READ THIS FAR DOWN STOP IF YOU DON'T WANT TO KNOW THIS IS ALL CAPS SO HEED IT.

According to Rollason's initial theories, the yeti stood in much the same relationship to humans as Neanderthals to Cro-Magnons, only the Neanderthals died out after the Pleistocene and the yeti, in their inaccessible mountain valleys, persisted into the present day. He's right and he's wrong: the yeti are another branch of the same evolutionary tree that produced humanity, but they aren't the outcompeted remnants hanging on in the shadow of the surging new species. They're the next step and they are waiting to inherit our earth. They don't have to eliminate us to get it. We're a volatile and warlike species; someday we'll blow ourselves away. All the yeti have to do until then is remain a myth. And so only Rollason will survive this expedition, because he's the only one who can be persuaded of this truth. (The young photographer might have been another, but he was wounded in one of Friend's traps and in staggering up over an icy ridge to find the yeti—heavily implied, telepathically drawn to them; that is another of their advantages over humanity—he slips and falls to his death. They might all have gone away safely if Friend had not been so determined to bring back a dead yeti if he couldn't have a live one. His associate Shelley is a notable hunter. He shoots one. It's indubitable, a dead body we never see beyond one long, sprawled arm, its blood-filled footprints the wrong shape for human feet. Rollason is horrified, haunted by the gentleness of its murdered face.* And the wind starts whispering. The Tibetan guide is already gone, screaming incoherently down the snow that he has seen that which man should not see. Shelley dies of an apparent heart attack, discharging dummy shells at something that might have been a real and vengeful yeti and might only have been a nightmare behind his eyes. Rollason hears a broadcast from a smashed-up radio, Friend the desperate cries of his dead colleague coming from the rocks where they buried him. The avalanche is what answers when when he fires into the dark.) Questioned by the lama of the monastery of Rong-ruk in the final moments of the film, Rollason gives his answer tonelessly, "I was wrong. What I was looking for does not exist," numb as a man who has seen the inevitable end of his own species in a pair of calm, intelligent, inhuman eyes. Maybe he even believes it. It doesn't matter. The secret is safe. And we'll be the myth someday.

* He tries to describe it out loud, which is one of the reasons the story kept suggesting itself to me as a radio play; we very rarely see anything onscreen that is not identified by the characters. See Friend and Rollason, discussing the yeti tooth in its casing of engraved silver: "Now, watch. The ornamentation hides the join, but it finally does unscrew and you see—" "A tooth!" "In the Middle Ages, it was the usual thing to preserve bits of tooth and bone from the bodies of saints. That's what that is, a reliquary—but of course you'd know more about that, doctor." "It's unbelievable. Look at the size of it!" Etc.

no subject

Not at all what I was expecting: better.

(I feel myself fading into myth already...)

no subject

Thank you, Nigel Kneale!

Glad you liked.